Small Review for the 6th C.A.J. Artist in Residence Program

“Abel Barrosso and Cuban Contemporary Art”

The exhibition depicted the present status of Cuban art from the so-called third generation artists born after the Cuban Revolution in 1959. Abel Barosso (born in 1969) was invited first, and then Sandra Ramos (born in 1969), Julio Cesar Pena (born in 1969), and Yendris Patterson Ricardo (born in 1970) were selected after discussion with Barosso.

The artists of this generation have all experienced the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the socialist bloc, and a nation existing in between capitalism and socialism, or a nation in an indecisive state, through their actual societal experiences including their activities as an artist. In the times of ‘periodo espacial’ (economic crisis or emergency state) in the early 1990s, people reduced to poverty tried to emigrate from the country by crossing the ocean and lost their lives. This tragedy in a country bordered with water, which is both a passage and barrier to the outside world, drew attention from over the world. What the artists saw in common here may be the various ‘límite’ of Cuba, while complex thoughts regarding the world across the water (adoration and hatred of the capitalist nation of the United States) accumulated in themselves from their younger days.

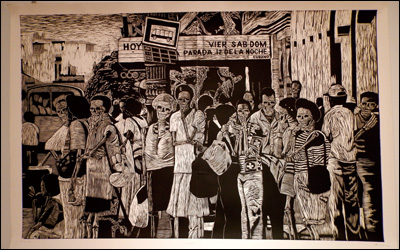

Sandra Ramos, one of the artists for the Venice Biennale in 2013, had taken this to be a problem of insularity and expressed it in various media such as oil paintings, block prints, collages, and objects. In her latest works, an animation called “DOMESTICACION” drew attention. In this animation, a Spanish man (with a Columbus-like appearance), an American (possibly Uncle Sam?), and a Russian (possibly Lenin?) tries to capture a crocodile (the Cuban island). Characters in a newspaper comic who were popular in the early 20th century such as Revolio, the icon of a Cuban farmer or El Bobo, a good natured commoner, resist Uncle Sam, who personifies America. It expressed the history of inveigling Cuba, which was first started by the Spanish.

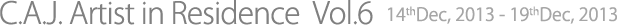

Julio Cesar Pena who won the Grandpre in the International Print Triennial in Kanagawa 2001, certainly saw the physical ‘límite’ of Cuban citizens while experiencing the poverty of ‘periodo espacial’ which was expressed in “La Parada” (2001). He depicted a group of Havana citizens waiting for a bus late due to a gasoline shortage in a large monochrome wood print, which was inspired by the serial caricatures of calavera by a Mexican artist, Posada. (For your information, there is a great Cuban movie called “Lista de Espera” that tells a similar story about an intercity bus.)

Yendris Patterson Ricardo, who is the youngest of the four artists, also uses the icons of Cuba, such as parma real, the Cuba island, or the national flag in a symbolic way. In his works, “Bandera con estrella” (flag with a star) and “Trazos de mi jaula” (the outline of the cage), the star (estrella), the symbol of Cuba, is locked in a gauze cage. The work can be interpreted in many ways. It can be associated with the economic sanctions imposed on Cuba by the United States, but it may also be interpreted as the closed situation which comes from insularity that the artist wanted to express. In fact, he moved out from Cuba, and works as an artist based in Spain. Not only Ricardo, but also Ramos has moved to the United States from last July, and many other artists to Spain, Canada, the United States, and other oversea countries. This may be the influence of a bad informational environment.

Finally we come to Abel Barosso, who stayed in Japan and engaged in the CAJ-AIR residence program. His works are related to the issues described above, for his greatest concern has always been in digital communication tools and ‘límite’ could be described as his keyword.

In 2009, President Obama directed Cuba to allow U.S. companies to establish improved communications between the United States and Cuba, including fiber-optic cable and satellite telecommunication facilities linking the two countries to lift some restrictions. However, no progress has been made yet, and this is one of the reasons that access to overseas websites and Skype is limited though e-mail to foreign countries is not (“Cuba, a Sturdy Country” Masuo Nishibayasi, 2013, Urban Connections). Mr Nishibayashi touches on Cuba’s sense of vigilance toward the freeing up of communications due to the effect it may have on domestic affairs.

At any rate, liberation of digital communications is a priority issue for an island country bounded by water (Cuba was working on laying marine cables to Venezuela from 2011, but is still using Internet oversatellite. On my visit to Havana in 2011, citizens stated defective cables from China as the cause of this failure.)

In this show, Barosso exhibited a huge wooden USB sculpture. He continued to create works with cellular phones and touch panel phones as a subject since he left a strong impression in the art scene by counterposing a humorous Mango brand desktop with the Apple computer. In his long pursuance of the same motif, he must have wanted to present the ‘límite’ of Cuba, and that the global progress of information and communication technology means only an information gap for him. We cannot resist appreciating his work with a wry smile when we see his un-portable USB which is adverse to its original function, and imagine the size of a PC which would be compatible with this accessory. Barosso’s work is comprised of criticism and irony to the late digital communication environment. His style that turns desire of freedom of communication into an art work is, in a sense, the same style that many artists in Cuba have chosen in an age when the country was strictly controlled by socialism. In that context, the works of Barosso could be seen as challenging ‘límite’.

Cuba, a solicalist country, has various ‘límite’ including its relationship with the United States, however, it is important that the artist approaches and asks themselves about these issues, and hopes for some kind of breakthrough. I hope that you can discover such possibilities of contemporary art in this exhibition.